Nizhoni Ranch News

Do You Know The Way to Santa Fe?

Celebrate Native art and culture at the largest and most prestigious intertribal art market in the world. Purchase jewelry, textiles, baskets, beadwork, carvings, sculptures, and drums directly from more than 1,000 of the “best of the best” Native artists, representing dozens of Tribes. And don’t miss the Indigenous fashion show, as well as the music, dance, storytelling, and comedy performances.

100th Annual Santa Fe Indian Market on the Plaza!

Free and Open to the Public!

No tickets necessary.

8:00 am - 5:00 pm

Free and Open to the Public!

No tickets necessary.

9:00 am - 4:00 pm

- Beth Barth

2nd Phase or 3rd Phase? Actually In-Between!

It is inspiring when Navajo rug collectors are born. Many immerse themselves so deep it is not long before they become experts. This collector is a perfect example of when the student becomes the teacher.

Please enjoy the following article!

May 1, 2022

Somewhere, Sometime, Somehow In-Between

by Ed B. from Minnetonka, MN

Somewhere, deep in a canyon or atop a high mesa, early Pueblo wearing blankets became the inspiration for the The First Phase Chief-Style blanket, or “beeldlei” in Navajo. This style was a simple broad striped weaving made of native hand-spun churro wool, wider than long and so tightly woven that it shed the rain. These blankets kept one safe by offering protection from the elements. Expensive to trade for, Navajo blankets became highly sought after as a sign of important social status and wealth. Hence the name Chief-Style Blanket.

Sometime in the 1840’s, The Second Phase of the Navajo Chief-Style Blanket began to evolve. The arrival of crimson colored cloth and yarns into the Navajo region and renewed experimentation with designs produced rectangular blocks and bands in the new colors. Positioned onto the simple broad striped pattern, this arrangement created the illusion of space by establishing a stable figure-ground relationship. When small shapes are placed upon larger shapes, the larger shapes are understood to be the background.

Somehow, by the 1860’s, the rectangular blocks and bands were slowly being replaced with triangular and diamond shapes that would define the Third Phase Chief-Style Blanket. Some shapes grew so large that they seemingly reversed the previous figure-ground relationship of the earlier Second Phase.

In-Between, there were early design ventures and continued experimentation with new shapes, colors and yarns that incorporated both the rectangular blocks typical of the Second Phase, combined with early stepped triangular shapes. Examples of this design combination are very rare.

In this early transitional or variant blanket, 1860-1870, stepped triangular shapes have just germinated, appearing to grow out of the straight bands of the Second Phase borders. Observe how these new shapes seem to burst into the broader striped areas. These triangular shapes help to create a newly defined border-contrast phenomena which is surely intensified by the triangular shapes when compared to the earlier straight bands. There exist only a few examples of this blanket design. Some refer to it as simply a Second Phase Variant or an early Third Phase.

- Beth Barth

Sandpainting : Father Sky Mother Earth

Sandpainting : Father Sky Mother Earth Navajo Weaving : Historic : JV 121 : 68" x 74" (5'8" x 6'2") : $18,000

Navajo Sandpainting - Father Sky, Mother Earth weaving from the Male Shooting Chant and used in various other chant ways.

The first creation of the Great Spirit was Father Sky and Mother Earth, from whence all life sprang.

The stars, sun, moon and the constellations are shown on the body of Father Sky. The zigzags crossing his shoulders, arms, and legs form the Milky Way. From the bosom of Mother Earth radiates the life-giving energy of the sun, bringing fertility to the womb of Mother Earth, from whence springs the seed of all living things. The 4 sacred plants shown are: Tobacco, Corn, Bean and Squash.

Mineral, vegetable, and animal – all things grow, mature, bear fruit, and fall. They all return back to the source from which they came (represented by the ovals at the bottom of Father Sky and Mother Earth).

The bat, the sacred messenger of the spirit of the night, and Big Fly or Sacred Fly guard the sand painting. The Rainbow Bars allow the Holy People to translocate instantaneously.

| Style | Sandpainting |

| Weaver | Unknown Navajo |

| Date | circa 1930s |

| Size | 68" x 74" (5'8" x 6'2") |

| Item # | JV 121 |

| Learn more about Sandpainting weavings | |

Contact us for more information at nizhoniranch@gmail.com or 520-455-5020.

- Beth Barth

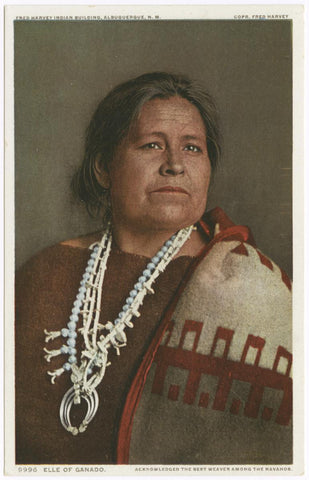

President Roosevelt and Elle of Ganado

What do President's day and Navajo weavings have in common? A wonderful 2001 article published in "Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies" brings both together in a way which helped shape the nation. Please grab a cup of tea, sit back and let your heart be filled.

Elle Meets the President: Weaving Navajo Culture and Commerce in the Southwestern Tourist Industry(1)

During the spring of 1903, President Theodore Roosevelt included a two-hour stop in Albuquerque while on a speaking tour through the western territories. the Commercial Club of Albuquerque chose a Navajo woman, called Elle of Ganado, to weave a gift for the president - a textile rendition of his honorary Commercial Club membership card. Club members provided the design, which Elle wove quickly in hand-spun red, white, and blue yarn.

During his tour of Albuquerque, Roosevelt visited the Commercial club, where he received Elle's blanket, and he stopped by the Alvarado Hotel's Indiana Building, where he met the weaver herself. An Albuquerque newspaper reported that upon meeting the weaver, the "president gave her a hearty shake and told her how much he appreciated her work. The little speech was interpreted and pleased the Indian woman beyond expression."

Although her own thoughts were apparently "beyond expression," Elle's image spoke volumes to turn-of-the-century Americans, showing New Mexico as not only conquered, but commercialized, safe for investment and safe for statehood.

Indeed, Commercial Club members orchestrated this performance as part of a statehood campaign, a drive for integration into the social, economic, and political life of the United States, an effort that would not pay off for nearly ten more years.

Elle and the president's meeting suggests ways in which race and gender, regional and national politics, culture and commerce interacted and were inextricably linked as the twentieth century began.

The pivotal role that Elle played in Roosevelt's visit reveals that while we tend to think of women like Elle as marginalized historical figures, they were far from peripheral to the unfolding of the twentieth-century American history. Not only can we better understand such women by placing them within the larger economic, cultural, and political context of their times, but we can better understand that context by putting a woman like Elle at its center. Elle of Ganado, also called Asdzaa Lichii' (Red Woman) in Navajo, was born to the Black Sheep Clan and lived in the southern part of the Navajo Reservation near the Hubbell Trading Post in Ganado, Arizona. She might have been about 50 years old at the time she met Roosevelt, and she lived until 1924. She was acknowledged as the best weaver among the Navajo.

The pivotal role that Elle played in Roosevelt's visit reveals that while we tend to think of women like Elle as marginalized historical figures, they were far from peripheral to the unfolding of the twentieth-century American history. Not only can we better understand such women by placing them within the larger economic, cultural, and political context of their times, but we can better understand that context by putting a woman like Elle at its center. Elle of Ganado, also called Asdzaa Lichii' (Red Woman) in Navajo, was born to the Black Sheep Clan and lived in the southern part of the Navajo Reservation near the Hubbell Trading Post in Ganado, Arizona. She might have been about 50 years old at the time she met Roosevelt, and she lived until 1924. She was acknowledged as the best weaver among the Navajo.

At the suggestion of trader John Lorenzo Hubbell, she and her husband Tom began spending substantial periods of time in Albuquerque beginning in 1903 after the Fred Harvey Company opened its Indian Building as part of the Alvarado Hotel complex at the Santa Fe Railroad depot. Together with other Navajo and Pueblo families, they worked as arts and crafts demonstrators within the burgeoning southwestern tourist industry.

You may read the rest of this fascinating article online here: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3347066

Navajopeople.org has an interesting piece about Elle's husband Tom here: http://navajopeople.org/blog/elle-ganado-wife-of-tom-ganado/

1Moore, Laura Jane. “Elle Meets the President: Weaving Navajo Culture and Commerce in the Southwestern Tourist Industry.” Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies, vol. 22, no. 1, 2001, pp. 21–44., www.jstor.org/stable/3347066.

- Beth Barth

Meant to Be

You may have heard the saying, you don't choose a weaving, a weaving chooses you.

By the photo one would jump to the conclusion that the wall color, furniture and wall size were chosen to compliment this incredible rug woven by Master Weaver Cecelia Nez. Especially since it was awarded the Gallup Inter-Tribal Indian Ceremonial top gun award, Best of Show in 2014. Not even close. All it took was minor furniture rearranging and voila.

Sure seems this weaving chose it's new owners well!

- Beth Barth

Churro Sheep : Back from the Brink!

For hundreds of years Churro sheep have been the center of Navajo life, yet the animal was nearly exterminated by outside forces.

Steve started working with Navajo weavers in the early 1970s and in the 1980s. He was very interested in improving the Navajo weaving quality by distributing better wools to some of his better weavers. During this time it was New Zealand Romney and Lincoln wools he would distribute to some of the better weavers in the Wide Ruins and surrounding areas. Many of these works were featured in his book The Fine Art of Navajo Weaving.

In the 1990s the economy was not very good and the natural dyes of the Wide Ruin weavers were copied commercially so the uniqueness of their weavings was compromised in value. At this time, Navajo weavings were missing something. Steve met with an old friend, Ray Dewey, in Santa Fe and they discussed how the quality of Navajo weavings could be improved at this point in time. The answer was the wool and the dyes.

The best weaving wool for the Navajo rugs and blankets is the Churro sheep wool. The historic pieces that have been present since over 100 years ago are clear evidence that the Churro wool is the best and only becomes better with time. This conclusion planted the seed to bring Navajo churro wool back to the loom. There were existing efforts to revive the Churro sheep since it was on the endangered species list, but nothing to improve genetics enough to have a high quality weaving wool. Navajo churro wool was the first weaving wool of the Navajo Nation because of its low lanolin content, long staple and translucent qualities. Bringing the churro sheep back to the Navajo weaver and the wool back to the loom was an important goal for Steve and Gail.

Steve was able to find the source of the Navajo Churro Registry where the genetics were being perfected for a better fleece. The next step was to find dye artists who were willing to dye the wool by hand for what would later be called the 'Navajo Churro Collection'. Though it seems like a simple thing, this took several years to put together. Moving forward with the process, the next step was reaching out to the best weavers on the Navajo reservation who were willing to use the Churro wool. The weavers were thrilled to use the wool, loved the new colors (Indigo, Cochineal and the highest quality dyes from Switzerland). With that, the Navajo Churro Collection was born.

The result of this project is history making in itself. For one thing the Navajo Churro Sheep are no longer on the endangered species list. Some of the very best master weavers of the Navajo nation are able to work on projects in the Navajo Churro Collection that they otherwise would not be able to do. They are given the very best wool which is hand dyed and custom spun ready for them to weave on their loom; the Nizhoni Ranch Gallery supports them through the weaving process even if it takes years for them to complete. A registry is kept of each weaving documenting the weaver, a photo of her, and the weaving. It is very important that in 100 years from now, the weavers will be recognized for their work.

The Navajo Churro Collection Weaving project is playing a part in preserving the Navajo weaving art in the Navajo culture. The Navajo Churro Collection celebrates the Navajo weavers and the art of the loom. The Nizhoni Ranch Gallery exclusively offers these weavings to the world, which represent some of the finest Navajo weavings ever made. Steve and Gail will continue their work and hope that one of the benefits of this project will be for young Navajos to take up this very difficult and beautiful art form, as it is a legacy well worth preserving.

- Beth Barth

Carding & Spinning Sheep's Wool for a Navajo Rug

Navajo weaving is both an art form and a labor of love. That’s because these highly-detailed rugs, blankets and weavings aren’t just for comfort; they tell an historic tale of a proud people through beauty and innovative creativity.

The origin of these well-woven textiles may have been passed down in story from Spider Woman who taught the first weavers to weave by using sunlight, white shells, lightning and crystals.

Here is more information about the historic methods of working with the wool after it is shorn from the sheep.

Traditional Hand Carding

Traditional Hand Carding

Historically, fleece and fibers were prepared before they could be used for weaving. Hand carding is the process of separating and straightening wool fibers using wooden paddles with wire “teeth” or bristles.

It works like this: the top “card” hooks its teeth into the wool in one direction, while the bottom “card” hooks its teeth in going the opposite direction. The weaver then works to gently tease and pull apart the wool creating evenly distributed layers, varying fiber lengths, eliminating any foreign matter inside, and improve fiber resiliency.

There are also two types of teeth which can be used—coarse and fine. The coarse cards are for fibers like mohair or wool, while the fine teeth can be used on soft fibers like cotton or angora.

Spinning the Perfect Thread

There are many forms in which to spin wool and the Navajo have a few techniques that can be used to form the perfect thread. The most famous and historic method is the Navajo spindle, also known as a drop spindle.

This type of spindle is generally categorized into three classes—center whorl, bottom whorl and top whorl. They all have varying degrees of speed and balance, but they can also produce different threat thickness. These “handspindles” involve spinning a stick with a weight top while the yarn twists and winds around the shaft.

Most of the historic weavings on our website are made with hand shorn, hand carded, hand spun Native Wool.

- Beth Barth

Don't Fall for a Knock Off Navajo Rug!

Oh, the thrill of stumbling across a beautiful weaving at a spectacular price. Here at Nizhoni Ranch some of our clients have interesting stories about coming across an estate sale, consignment shop, garage sale or auction house where they hit the jackpot or crapped out.

Yet, the old adage "if something sounds to good to be true, it probably is". Probably is the downfall for some. The definition of probably is: without much doubt, reasonably true, likely. Probably is trouble - it gives a ray of hope to those who want to believe.

Then there is the Antique Roadshow situation. As AR passed through Tucson in 2001 a man took in a blanket he inherited from his grandmother. The blanket was originally given to his great grandfather by Kit Carson. The blanket was used on his bed as a child then later sat on the back of a chair for years. After watching the appraiser almost pass out and then being whisked away by security, he was told the weaving was a Ute First Phase Blanket, circa 1850's. A national treasure worth (at that time) $350k to $500k. Today that very weaving is valued somewhere around 1.5 million. A beautiful story that remains one of AR's finest moments - a must see and a tear jerker!

So what is one to do? Pay close attention to:

1 - Fringe

Almost all Navajo weavings will not have fringe. There are only 2 exceptions. Textiles woven with Germantown yarn. Fringe is added after the weaving is completed. Take a look:

The other Navajo weaving that has fringe (only on one end) is a Gallup Throw. Gallup throws became a popular and inexpensive tourist souvenirs. They are woven with a cotton warp. Once finished the warp is cut then knotted. A typical contemporary Gallup Throw sells for somewhere between $50 to $100. See below:

Ganado Throw

2. Warp

Warp strings run vertically and made on a continuous loom that contains the actual warp threads. You can check this by running your hand along the side of the rug to feel whether the warp threads run the length of the rug or whether they’ve been cut. In Mexican-made copies, the warp strings run horizontally and threads are cut and then sometimes hidden, making it more difficult to detect.

Navajo woman weaving on an upright loom with vertical warp strings.

3. Lazy Lines

Lazy lines appear as a diagonal line in the weave of the fabric. During the weaving process, the rug maker would move to work on adjacent sections of the warp, resulting in the subtle diagonal lines referred to as lazy lines. Note: not every Navajo weaving has visible lazy lines.

Lazy lines at diagonal angles

4. Cost

Like all Navajo weavings, the values vary based on the age, quality, size, design complexity and condition. A 3 x 5 contemporary weaving, with good design, good condition and nice wool starts around $ 2,000. Below is a contemporary Teec Nos Pos / Red Mesa weaving. Teec Nos Pos is one of the most intricate of designs. This was woven in 2017 by Elsie Begay and measures approximately 5' x 9', $9,000.

The U.S. Department of the Interior, Indian Arts and Crafts Board have published a very informative pamphlet on How to Buy Authentic Navajo (Dine') Weavings. To view the publication go to: https://www.doi.gov/sites/doi.

Bottom line, buy through a reputable source and keep all receipts and other documents. Reputable, meaning they stand behind the weaving and if it's not as portrayed, they will return 100% of what you paid.

If you are fortunate enough to have a weaving pop up outside of a gallery or reputable dealer and told it is Navajo, buyer beware. We believe if you love a weaving, the price is right and will still be happy if the weavings turns out to be something other than Navajo - go for it!

Happy Hunting!

- Beth Barth